There’s this notion among moms: Whatever you do, don’t be “that mom.”

It drives me bonkers.

I’ve had a number of friends in the hospital recently with their kiddos. Some are medical parents, others are experiencing their first hospitalization. I often hear the phrase “that mom,” as in I don’t want to be “that mom.” It comes up in nearly every conversation.

When Eloise is in the hospital, with every single poke, catheter, and procedure, I want to trade places with her and scream, “Stick me instead!!!” I know Zach feels this, too. As medical parents, we experience the duality of emotions during an admission. There’s immense gratitude for healthcare staff and medical interventions that have kept Eloise alive. And there’s also significant trauma from the close calls, mistakes that shouldn’t happen, and impossible decisions during family meetings.

It’s complicated. There’s personal trauma from Eloise being very sick and systemic trauma from an institution we’re supposed to trust. An attending doctor once told Zach and I that we should go out on a date because the hospital has the world’s best babysitters. She probably said something like, “Mom and Dad, you guys should go out on a date!” I laughed. There’s a reason (or many reasons) we never leave Eloise’s bedside.

And yet, as Mom and Dad, our experiences are different. Societal pressures and expectations of women play into being a mom in the medical setting. I often feel like I can’t get it right. I am observant and perceptive, and I am sensitive to what other people think of me. I wish I didn’t notice or care, but I am human. It’s an isolating experience for me as a mom.

some stories specific to the hospital

My husband changes *one* diaper, and he will receive praise for his noble act of service… for the duration of our stay. Seriously.

“I can’t believe you changed a diaper, Dad!”

“Dads never change diapers around here!”

“I haven’t seen a dad change a diaper in a long time!”

Do you know what’s said when I change a diaper? Nothing.

I sometimes do an experiment when aides or nurses come in to check vitals. Here’s what I’ve found:

If Zach is standing next to the crib, Eloise’s diaper is automatically changed, no questions asked. If I am standing next to the crib, Eloise’s diaper goes untouched. When this happens, I sometimes ask them to change her diaper. I get an eyeroll or a begrudging yes.

It should go without saying that, of course, this phenomenon doesn’t happen with every aide or every nurse, but it happens more often than you’d think. Eloise gets C. diff when she’s on IV antibiotics. Let me tell you, it involves a lot of stinky diapers. Zach and I both do our part because we are her parents.

While Zach is championed for changing a diaper, he isn’t trusted by healthcare workers to answer questions about Eloise. When the doctor, resident, or nurse come into the room, questions tend to be directed at me, mom.

They start with,

“So, Mom, how did the night go?”

“Mom, we got the test results back.”

“Mom, what’s your preference?”

Two years ago during an admission I was using the restroom when Eloise’s nurse came into the room. He knocked on the door and proceeded to ask me questions about Eloise’s feeds. Zach was in the room and answered the nurse’s questions… and the nurse continued to ask me questions through the bathroom door.

The nurse’s questions centered around my breast milk. I was still pumping at the time, and my milk had either gone missing or had not been sent to the hospital’s milk lab to get properly thawed and prepared. One nurse actually recommended we start bringing our own mini fridge during admissions because so much of my milk had been lost. Another time we had two separate stays a couple of weeks apart, and ten ounces of my breast milk had been magically discovered in the freezer on the intermediate unit. I guess it’s a good thing we came back?

As I discussed one of these breast milk predicaments with the nurse, I sat on the toilet wondering if I should flush or wait.

I feel the pressure of always being on. Ready to meet the revolving door of healthcare professionals who walk into our room. Ready at an instant to rattle off Eloise’s date of birth, medications, and feeding schedule. Her information is so ingrained that I cannot remember my own date of birth or medications when I have doctor’s appointments! I’m prepared to answer questions on the toilet, after getting woken up, and at all hours of the day. It is depleting to feel the sole responsibility of answering all questions in addition to the vigilance and advocacy that is required to ensure Eloise receives the best care. Here’s the thing – it doesn’t have to be my sole responsibility if healthcare workers trusted my husband or directed questions at both of us rather than only me.

This would sound like,

“So, Mom and Dad, how did the night go?”

“Mom and Dad, we got the test results back.”

“Mom and Dad, what are your preferences?”

Zach is equally involved in Eloise’s life, and, in addition to changing diapers, he is fully capable of answering questions.

I can’t avoid the reality that Zach’s voice matters more than mine. Even though he isn’t trusted to answer questions about Eloise, his requests or suggestions are taken seriously. We joke that I have to say something ten times for his every one, only, singular time to get the same result. It’s not really a joke, but if we don’t laugh we’ll cry, right?

The nurse who I chatted with while using the restroom later told me that I talk too much because I am just a mom. He directed this comment at Zach with a tinge of misogyny. The nurse went on to tell us about his medically complex daughter, how his wife talks a lot when their little girl is admitted, how she doesn’t really know what she’s talking about, and why this embarrasses him in front of all the doctors since he’s a nurse on the General Pediatrics unit.

Why did he feel the need to tell me that I talk too much because I am just a mom?

Because I requested that Eloise’s new seizure medication be given with the rest of her medications. During this admission, Eloise had her first seizure and was consequently prescribed Keppra. She needed it twice daily, and it was scheduled at a wonky time. I thought it would be in everyone’s favor to clump her medications together. Eloise could rest with fewer people in and out of the room, and the nurse would have one fewer trip up and down the hallway. The nurse refused to switch the time. He also refused to leave Eloise’s room until Zach told him to get out.

Another Story

Perhaps the following story will be more relatable to all moms, not just those who find themselves interacting with healthcare more than the average person.

Zach and I attempt to split the caretaking responsibilities. It’s not perfectly down the middle, but it’s what works for us. I handle most phone calls and communication with doctors, and Zach handles medication refills and pharmacy phone calls. He also picks up the medicine. We purposefully use a pharmacy that’s open until 10pm, so that we have flexibility with the pickup time. I am with Eloise all day, and Zach takes her when he gets home from work. They cook dinner together, he does the breathing treatments and shaker vest at night, and then he puts her to bed.

Eloise currently receives five different telehealth therapies. Depending on our schedules, Zach and I take turns attending the therapy sessions with Eloise. Because we share this responsibility, I have asked for both of us to be included in the text and email communication. We communicate with most of our therapists directly, and I prefer to have a group chat.

There have been countless times when the Zoom link is sent to me on a day when Zach is the parent attending the session. I then have to send the link to Zach when I inevitably receive a text from the therapist asking why I haven’t logged on. My response has started including something about contacting Zach and then sharing his phone number (even though I include it on every form).

We are well established with our therapists now, but in the beginning it was frustrating to train others on how to communicate with both of us. It took several trial and error sessions with each therapist to get things running smoothly. When Eloise has five therapists, it’s a lot. I’ve noticed a similar situation happening with communication from Eloise’s preschool. I haven’t asked for both of us to be included in the emails because sometimes it’s just easier to forward the emails to Zach. I have found that even if I “cc” Zach on an email, he is hardly ever included in the reply. I revert to handling it myself, you know?

I understand that only one person can receive a phone call, but I wonder why it’s not automatic to email and text both parents, especially if a parent has requested this? We are very much a team, and sometimes it feels as though we have to train others on how to communicate with both us rather than only me.

Concluding Thoughts

The point of sharing these stories is not to be petty about diaper changes or answering questions while sitting on the toilet or getting belittled by a nurse or sharing Zach’s contact information over and over again. It’s about something deeper. I want to shed light on the reality that moms and dads are treated differently, and yet, moms get the negative label while dads are praised for doing the bare minimum. I don’t think it’s fair. I shared only a few stories, but the truth is I have countless stories to illustrate this reality. Whether it’s a hospital admission, doctor’s appointment, or therapy session, moms are expected to hold it all together while also being judged the harshest.

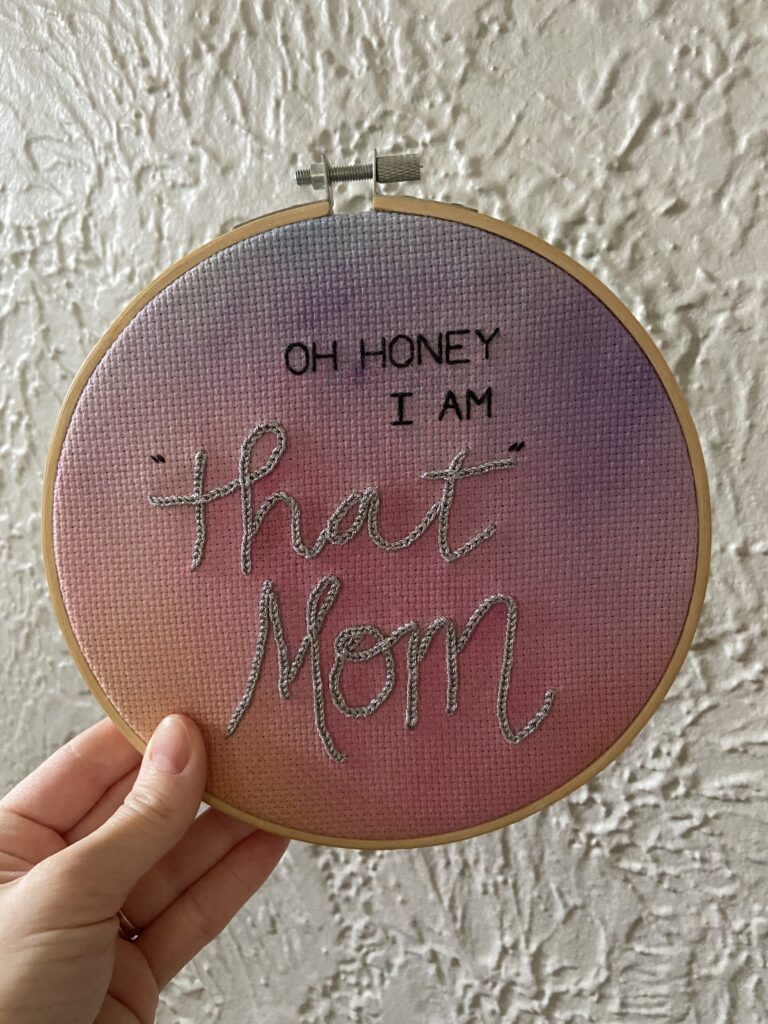

There’s no such thing as “that dad.” But I get the label of “that mom.”

“That mom” who no mom wants to be.

Is it really a bad thing?

“That mom” who asks for specific physicians, who asks for second opinions, who asks questions, who asks for clarification, who asks to speak with management when big issues arise, who asks for diagrams, who writes everything in a notebook, who speaks up when safe practices are not being followed, who insists on sticking to a schedule because there’s a thin line between our hospital life and home life, who advocates for both herself and her daughter.

For some reason, “that mom” is viewed as difficult even though she does her job.

Don’t be “that mom” but be an advocate. Don’t be too blunt or forward or inquisitive or protective or fierce but be a mama bear and wear that cute mama bear shirt, girl.

I mean, really, is this what people want? Wear the cute mama bear shirt and sip coffee out of the mama bear mug? But don’t act like a mama bear?

How should a mom act? If I say too much or show too much emotion, I am labeled as “that mom.” If I don’t say enough or lack emotion, I am labeled as an absent mom.

Sometimes I am both. Emotional and numb. Am I allowed to exist in the space between “that mom” and absent mom?

For the record, I think it’s okay to be “that mom.”

“That mom” who is fierce, who is kind and audacious, who is a little sassy, who demands respect, who wants the absolute best for her child, who asks questions and wants answers and will continue to ask questions when the answers don’t make sense, and who appreciates the help, care, and knowledge from all who come alongside our family.

I might be considered difficult, but I’m also an advocate. More importantly, Eloise receives the care she deserves. Having a voice for her is not something I take lightly. If I don’t speak up for her, who will?

I also admit that I’m learning and growing. I sometimes look back on experiences and ask myself,

“Did I need to say that?”

“Did I need to pick that battle?”

“Did I make that clarification for Eloise or my own ego?”

One time during an admission, I told the resident something about the hospital being a shit show and how I thought it was hell. I probably didn’t need to speak these unkind words out loud, and I later apologized (even if it was when we were faced with the same resident a few weeks later for another admission). I regret and feel horrible about this interaction. I’m actually cringing while I type these words.

As I experience life alongside Eloise, I recognize that we have to interact with major institutions, such as healthcare and the school system, more often than most of my mom friends. As with any close interaction, whether it be with a person or an institution, we view both the good and bad through a close-up lens. Mistakes happen. Misinformation is shared. We don’t always see eye to eye. I’m coming to terms with the reality that we are playing a long game, and I cannot use my voice and advocate for change every single time Eloise is slighted. Maybe we all have a version of “that mom” we don’t want to become. Mine is something about becoming a jaded and bitter mom.

I guess what I’m trying to say is, I’m learning how to extend grace to others, and I wish the same grace could be extended to moms. A little less judgment on both ends as we all try to do our best.

And for the love of all that’s good, “that mom” is a mom trying her best.