This summer was the summer of getting back out there. We’ve spent much of the past couple of years in isolation as we’ve done our best to keep Eloise healthy. The warmer temperatures and outdoor activities allowed us to feel more comfortable with going out. We did things like going to local park district events, outdoor dinners with friends, the farmers market, and the zoo. I remember jokingly but truthfully telling a friend that this is the summer we’re getting back out on the town. It was a summer of reconnecting with friends we haven’t seen in awhile and engaging with our local community.

At the beginning of the summer, some of my feelings and observations took me by surprise, or rather, I was reminded of the ways our life looks different. Of course, I know Eloise’s life looks different from a neurotypical almost three-year-old. I have processed and grieved the loss of normal, but it felt like another level of processing and grief when I was faced with other people’s recognition of our differences.

“I’ve realized that I value the ability to blend in with a crowd, and I feel vulnerable and exposed when people stare.”

People stare at us, and it’s not just my social anxiety. I suppose we are a bit of a spectacle with Eloise’s bright pink adaptive stroller, a big red umbrella attached to the stroller (because insurance doesn’t cover the canopy), a fan blowing on her, and the occasional beeping of the feeding pump. I’ve realized that I value the ability to blend in with a crowd, and I feel vulnerable and exposed when people stare. Now I wear sunglasses, not to block the sun, but to block strangers’ stares. I recently listened to an interview with Khloe Kardashian, and she talked about how she wears sunglasses on the red carpet as a sort of shield. Never have I related to a Kardashian more in my life.

Rather than stare, I wish people would say something. Say hi. Say my daughter is cute. Say something about her outfit. Say she has a beautiful smile. Say something about her sweet setup with the umbrella and fan. If people don’t want to say something, then at least smile if you’re going to stare. I guess what I’m saying is please treat us like people and not just a sight to see. It has taken a lot of time and effort to get to a point where we try to engage in community events.

When I hang out with mom friends, I always come home analyzing a part of our conversation. Moms talk about their kids. Moms brag about their kids. Moms complain about their kids. In short, moms relate to other moms about their kids. There is inevitably a point in the conversation when I say something and then realize I’ve entered no man’s land. My mom friend can’t relate. I continue talking because I think an explanation is necessary. And then I feel myself getting anxious because

the tears are welling up and I really don’t want to cry or

I’ve gone too far or

I’m silly for trying to talk about something that I knew would be unrelatable or

I’m tired from having to explain everything or

I don’t enjoy talking that much, so now I’ve disassociated and feel like I’m watching myself explain something I’ve explained 100 times.

It’s weird to be in a position where I can relate to my friends’ motherhood experiences more than they can relate to mine. I know my friends want to be there for me, but it’s exhausting to explain so much of my experience. My therapist tells me that I can just stop talking when I begin to feel anxious. I think I so badly want someone to relate to me that I just keep talking in hopes that my mom friend *might* be able to connect with a snippet of my experience. Most of the time I leave the hangout feeling foolish and then swear off whatever topic I brought up. I also do this thing where I put pressure on myself to wrap up the conversation on a positive note. Did I crack a joke? (I firmly believe trauma makes people funnier.) Did I talk about the good? Did my friend smile or laugh?

Another question I ask myself is, “Did I interact with their kids?” I recently held a friend’s baby, and I felt so uncomfortable. I’m sure I looked noticeably uncomfortable. The baby was squirmy. The baby was flexible. The baby could move his arms and legs. In physical therapy vocabulary, the baby’s range of motion was excellent. I only held the baby for a few minutes before giving him back to his parents. Sometimes I hang out with kids around Eloise’s age, and I am always struck by the differences. I don’t know if I will see Eloise walk, which makes it strange to see a child her size walk and run.

And then there’s the neighborhood. There are plenty of kids. I observe some of them playing together while their parents chat. I can honestly say that I know more neighborhood dogs than kids. People don’t ask us to come over for playdates or watch their kids. But I was the dogsitter for two different neighbors this summer.

“What I want most of all is for Eloise to be treated like a little girl.”

I’ve become really sensitive to our life looking different. Like duh, our life looks different. In some ways, it’s easier to shelter ourselves from the outside world. Stay home. Don’t go to dinner with friends. Don’t go to the farmer’s market. Don’t try to honestly share the highs and lows. When we’re in our little bubble, our home is safe and normal. I feel vulnerable and exposed when I sense the recognition from other people. The recognition of raising a child with disabilities.

Kids stare and their parents shush them. I overheard a little girl say, “Oh! She’s so cute!” Her mom responded with, “Shh, don’t stare.”

What I want most of all is for Eloise to be treated like a little girl. If kids want to ask questions, it’s okay. I love kids’ natural curiosity and honesty, and I will always welcome their stares and questions. It feels dehumanizing when adults choose to avert children’s questions. The irony in telling kids not to stare when adults are the worst culprits is not lost on me. When adults respond with “Shh, don’t stare” or “We’ll talk about this at home” it’s a signal to the child that kids with disabilities belong in an “other” category. The “other” kids who we don’t play with or talk to or engage with.

A little boy recently wanted to say hi to Eloise, and I asked him to come to her left side because she cannot see out of her right eye. The little boy asked why. I told him this is the way she was born, and we all have features that make us unique. We talked about how it’s beautiful that one of Eloise’s eyes is blue, and the other one is brownish green. When the little boy moved to her left side, Eloise smiled at him, and the little boy was so tickled by her smile. Even though Eloise cannot say the word hi, she is able to say hi with her smile and coos.

I want to share about a few more positive interactions. I’m not just sharing to end on a positive note (I promise), but I share because I think disability makes people feel uncomfortable, and I want to believe that people genuinely desire to be kind and inclusive. The truth is disability is not something any of us are immune to. Anyone can become disabled at any time. Most of us know someone in our lives impacted by disability whether it’s a friend, family member, classmate, or neighbor. With this being said, it boggles my mind that we don’t know how to interact with disabled children and adults, and the gut reaction is to disengage. I want to share so that we can all treat others with kindness and inclusivity.

Early in the summer, we had a couple of interactions that gave me hope when I was feeling most discouraged.

Interaction #1

Maiden Reed & Stem at the Peoria RiverFront Market

Not only did a bouquet of fresh flowers brighten up my home each week, but Jess and Polly also asked about Eloise, made it a point to say hi to her, and complimented her outfits. We chatted about our girls sharing Peoria’s most beloved feeding therapist. It was a small thing that kept us returning to the farmers market every Saturday. I dealt with so much anxiety in our first couple of markets simply from the amount of eyes on Eloise. They are true gems, and I could count on them to treat Eloise like a little girl.

The takeaway: engage, do not disengage.

Interaction #2

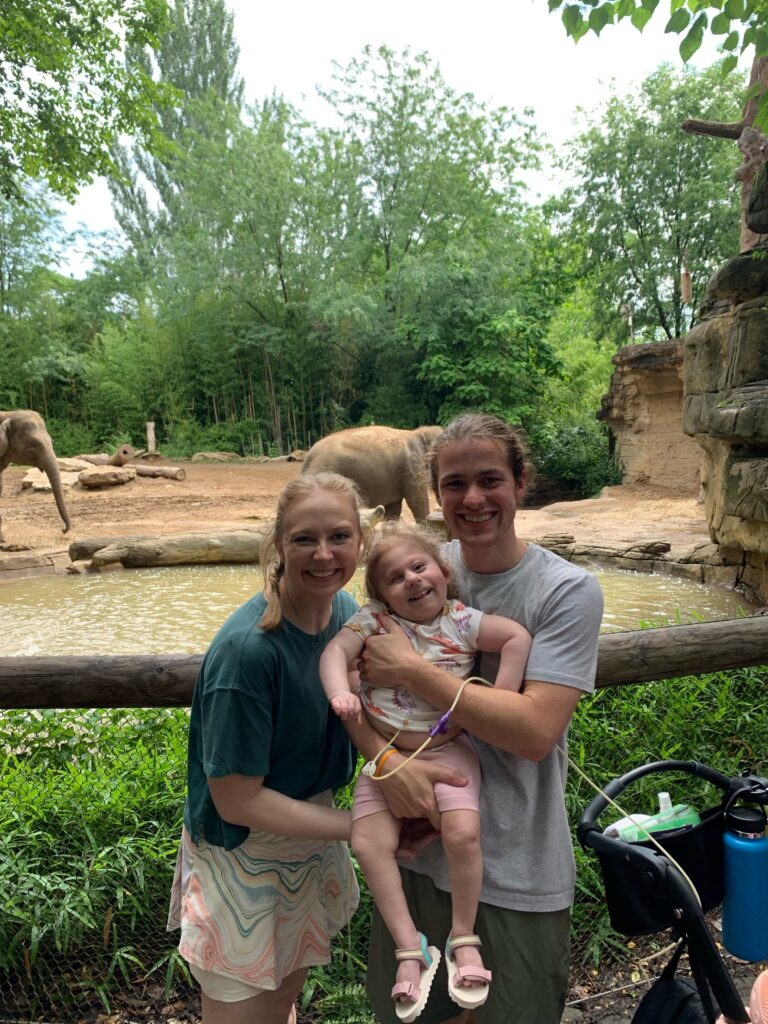

The Family at the St. Louis Zoo

We rolled into the sea lion show only a few minutes before it was scheduled to begin. A mom approached me and said that her family was in the accessible space a few rows in front of us. She wanted to say how it can be isolating and lonely to be on this journey of raising a medically complex kiddo, and we exchanged phone numbers. After the show we met her daughter Savannah, and I can’t tell you the immense relief I felt in this interaction. St. Louis was our first attempt to take a trip as a family, and this mom gave me the little boost of confidence I needed to keep trying to do “typical” things like going to the zoo.

The takeaway: medical moms are amazing. The support and understanding we have for one another is unmatched.

Here’s to being more inclusive and kind.